Farm for Dissent

GET THE #1 EMAIL FOR EXECUTIVES

Subscribe to get the weekly email newsletter loved by 1000+ executives. It's FREE!

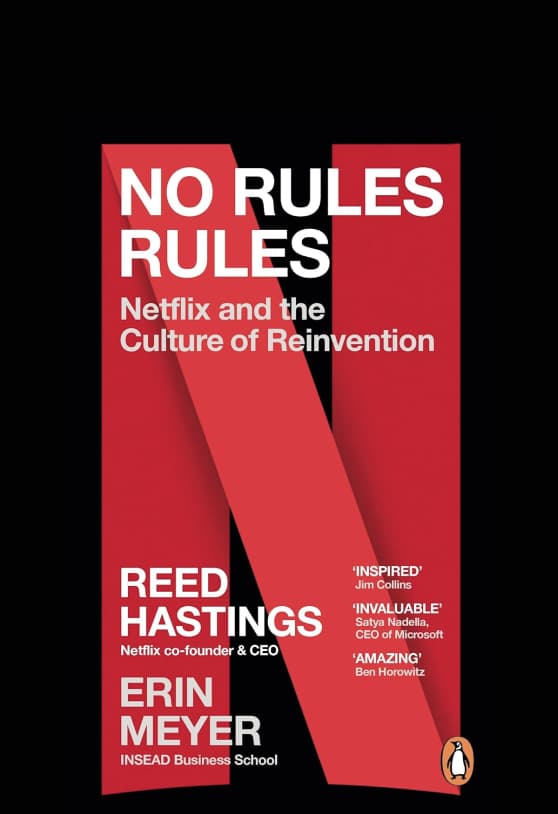

Picture this: You're in a Netflix executive meeting in 2007. Reed Hastings has just announced the decision to start streaming movies online – essentially betting the company's future on an unproven technology.

The room goes quiet. Everyone's thinking the same thing: "This could kill us."

But instead of moving on, Reed does something unusual. He starts actively looking for people who think this is a terrible idea.

A question that he might ask in that moment to everyone in the room is:

How would you rate this decision on a scale from -10 to +10 and why?

Welcome to "farming for dissent" – possibly the most interesting (but powerful) leadership practice you can implement.

The key concept here is that it's not good enough as a leader to just expect people to disagree with you, you have to actively farm for it.

You have to make a habit of it and you have to repeatedly force people to give you their honest opinion.

The Most Expensive Head Nod

Let's go back to the year 2000, Blockbuster had the chance to buy Netflix for $50 million. The Blockbuster executives sat in their fancy boardroom, nodded along with each other, and decided streaming would never catch on.

We all know how that ended.

But here's the thing – there were probably people in that room who thought it was a terrible decision. Who knows, maybe they had an insight into streaming.

One Blockbuster employee at least thought this.

In this video that has recently gone viral he talks about how he probably won't have a job in the future due to the rise of streaming.

I'm sure if Blockbuster had farmed for dissent back then, there would have been a few more people who would have spoken up.

Why We're Terrible at Disagreeing

Let's be honest – it's not easy to tell your superior their idea is bad.

I often sit in meetings where everyone agrees to a plan just because someone seems excited about it.

Don't even get me started on that person that you invite to a pub quiz event and then they constantly lock in the wrong answer.

So if this article does nothing else, when you go to a pub quiz next and you are not 100% sure of an answer, try some farming for dissent.

Now finally you might get that spot prize of coming second to last!

How Amazon Does It

Amazon has a practice that in their big meetings, they start with the most junior person in the room. Not the CEO, not the VPs – the person who probably still gets lost trying to find the bathroom.

Why? Because if the CEO speaks first, everyone else just nods along.

This is something that we have been trying at our work. I've found that it leads to far more interesting conversations and a lot more ideas being shared.

Some other things that these large companies do:

- Give people prep time to build their case against an idea

- Require written dissent before big decisions

- Celebrate when someone's criticism prevents a mistake

- Thank people for disagreeing (even if it makes the meeting run long)

Hastings thinks the key is making it systematic: "We have managers do things like 'what are three things you would do differently if you were in my job?' I would, every 18 months or so, do that with 50 top executives."

The Art of Farming for Dissent

Here's how to start, without making everyone hate meetings even more than they already do:

1. The "What Could Kill Us?" Game

Instead of asking "any concerns?" (which nobody ever answers honestly), try this: "Let's spend 10 minutes listing all the ways this could absolutely destroy us."

2. The Designated Dissenter

Pick someone each meeting to be the official party pooper. Their job? Find every hole in the plan. It's like being a movie critic, but for business ideas.

Sometimes it is easier to do it this way as it's a role that the person is fulfilling.

People love it because they get permission to say what everyone's thinking.

3. The Reverse Victory Lap

When something goes wrong, celebrate the people who tried to warn you. "Sarah told us this would happen three months ago, and we didn't listen. Sarah, you were right – we were wrong. Thank you for trying to save us from ourselves."

When It Goes Wrong (And It Will)

There is a massive caveat to all of this.

Reed Hastings only seeks out dissent from executives that he trusts and who have a track record of making good decisions.

The first time you try it, someone's going to take it too far and turn your nice team meeting into an episode of Dragon's Den.

Some common mistakes:

- The chronic dissenter (disagrees with everything, including lunch orders)

- The personal vendetta disguised as feedback

- The "I'm just playing devil's advocate" person (who's actually just being difficult)

Ultimately the mission here is to help the company.

But here's the thing – even the messy attempts are better than the alternative. Blockbuster-level mistakes happen in silence, not in chaos.

The Real Magic

The best part about farming for dissent isn't actually the dissent – it's what happens after people get used to it.

Teams get better at disagreeing without being disagreeable. Ideas get stronger because they've survived real criticism. And most importantly, people stop being afraid to say "I think this might be a terrible idea" when it matters most.

Hastings emphasises this point: "The best ideas can come from anywhere, but only if we're willing to look for them - especially in the places where people disagree with us."

For more on this you should read about how Pixar do it with their braintrust

Your First Step

Start small. In your next meeting, try this: "Before we move forward, I need someone to tell me why this is a bad idea."

Then wait. The silence will be uncomfortable. But what comes after might just save your company from becoming the next Blockbuster.

Remember: The goal isn't to create disagreement – it's to find the truth before it finds you. As Reed Hastings says, "Success hides problems." Sometimes the kindest thing you can do is farm for the problems while they're still small enough to fix.

Now, who wants to tell me why this article is completely wrong? 😉

Further Reading