GET THE #1 EMAIL FOR EXECUTIVES

Subscribe to get the weekly email newsletter loved by 1000+ executives. It's FREE!

Every once in a while, we witness something in sport that makes us question the whole game.

A moment that stands tall against the conventional, a moment where someone refuses to play by the rules everyone else takes for granted—and wins.

That for me was watching Anna Kiesenhofer cross the finish line in the Tokyo Olympics.

The Unlikely Contender

To recap, going into the race the Austrian was a relative unknown, with no professional team and no support staff.

She's an academic, a mathematician with a PhD, and she prefers to train alone, without the structured support system that most elite cyclists swear by.

Her odds of winning the race were 1:500 according to the bookies.

How did she do it?

Exactly the way you or I would, if we entered a race as an amateur.

SHE ABSOLUTELY SENT IT

You know when you are at a party and you are like, what would you do if you were in the Olympics and you tell your mates

"I would sprint from the beginning (of a 137km race) and hold on for dear life?"

That's what Anna did.

Photo by Sandro Halank, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0, CC BY-SA 4.0

She broke away from the pack early on and held on to win the gold medal (Austria's first ever gold medal in cycling).

This is absolutely incredible because studies have shown that riding in a peloton reduces wind resistance by 96%.

The People in the Race Literally Forgot She Was There

It was so good Annemiek Van Vleuten, one of the sport's most accomplished athletes, crossed the line celebrating, arms held aloft, thinking she'd won.

It wasn't until moments later that she realised—no, the gold had already been claimed by someone she hadn't even counted as a contender.

That's how far under the radar Kiesenhofer was.

SO... Was it a Rational Decision?

I've always wondered about the math behind that day. My intuition tells me that more cyclists should do this and so that is what we are going to explore now.

It's similar to how in the NFL teams should go for it on 4th down more often than they do.

I love these counterintuitive decisions that are actually the right ones.

My end goal here is that more people with 1 to 500 odds will be encouraged to absolutely send it from the start line so that we can collect a big dataset and study the results.

The Stats

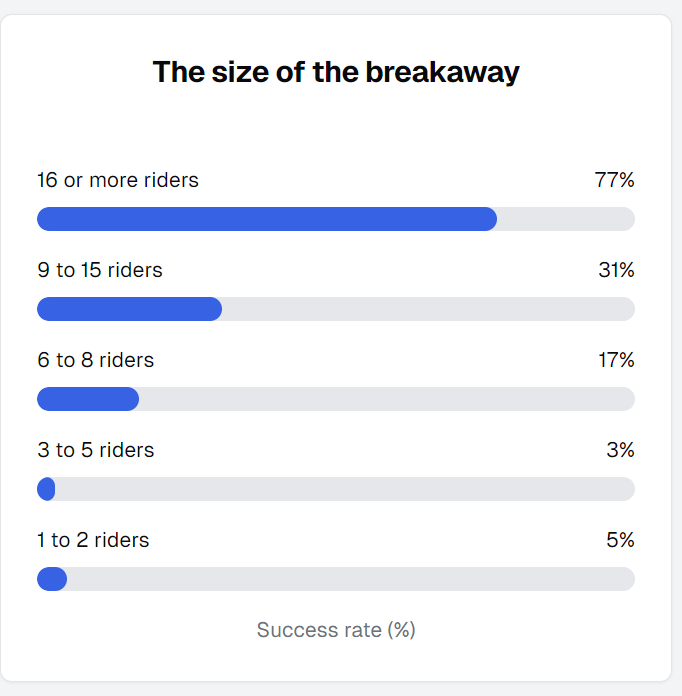

So the size of the breakaway is important to the odds of winning.

You want to have as big a group as you can. Interestingly though, this data is taken from the Tour de France and there were only 67 riders that day.

Anna initiated the breakaway with 4 other riders. So from the get-go we are down in the 3% odds of winning range.

Tour de France Breakaway Stats

- Only 39 breakaways succeeded out of roughly 140 stages over seven years

- With about 1,500 riders involved in breakaways, each individual had a 2.6% chance of winning

Already, we see Kiesenhofer's odds improving from 0.2% to 2.6%—a 13-fold increase just by being involved in a breakaway!

In the Olympic Race

Kiesenhofer was in a break of five, which initially seems disadvantageous. However, in the Olympic race:

- No team radios were allowed, creating communication chaos

- National teams, not professional teams, were competing, reducing organised chasing

These factors potentially neutralised the usual advantage of a large peloton, making her small breakaway more viable. Again, it still doesn't account for the harder wind resistance of being in a smaller group, but remember they literally forgot she was there.

This shows an important thing for Olympic cycling: you might not actually want to be in a peloton that is too big.

Realistically, by breaking away at the beginning of the race, you are essentially playing chaos theory and hoping that something happens that will give you an advantage.

The Course

From the Olympic website:

The women’s race will cover 137km, and the course will be even more challenging than at the Games in Rio. With a total elevation gain of 2,692m, the route will see the cyclists climb 1,101m more than their counterparts on the Carioca course in 2016.

The Tokyo course wasn't flat—it was hilly. This is crucial because:

- Only 1 successful breakaway occurred on flat stages since 2013

- Over 50% of high mountain stages were won by breakaways

- Almost 50% of medium mountain stages saw breakaway victories

Game Theory

From a game theory perspective, Anna Kiesenhofer's breakaway can be analysed using expected utility and probability theory.

Given her initial odds of 1 in 500 (P = 0.002), the expected utility of staying with the peloton was effectively near zero, as the probability of winning in such a scenario was extremely low.

By choosing the breakaway, she increased her probability of success to approximately 2.6% (P = 0.026), which represents a 13-fold increase in her chances of winning.

Cyclist's Breakaway Decision Tree

Additional Factors

Decision Analysis

Expected Value of Breakaway: $1600.00

Expected Value of No Breakaway: $10.00

Decision: It is rational to attempt a breakaway

As we have shown in our social media post, the odds of winning a medal are not the only thing that matters.

Even if she had not won, if she had been in the breakaway and been caught, that exposure is worth a significant amount of money in terms of sponsorship and potential followers gained.

Conclusion: The Rationality of Ripping It

Kiesenhofer's decision to break away early wasn't just gutsy—it was rational. She maximised her chances of success while minimising her downside risk.

In the end, Kiesenhofer didn't just win gold; she provided a masterclass in game theory and strategic thinking.

Her victory reminds us that sometimes, the most rational move is the one that seems the craziest to everyone else.

So the next time you are doing an 8k fun run and you are like, "I'm going to sprint from the start line and hold on for dear life," remember Anna Kiesenhofer.

Just make sure you have a PhD in mathematics first.