Why a 16th Century Queen Would Excel in Today's Tech Boardrooms

GET THE #1 EMAIL FOR EXECUTIVES

Subscribe to get the weekly email newsletter loved by 1000+ executives. It's FREE!

The Great Job Heist

Hi, my name is Chris, I run a company called Cub Digital and I keep waking up to find that my job has vanished.

Not in the traditional sense - my desk is still here, my computer still works, but as I scroll through my news feed, I constantly see this: "AI Writes Code Better Than Humans."

I keep wondering, is this actually true? Are we all about to be replaced by robots? I'm not alone - across the globe, millions of people in the software industry are waking up to the same existential dread. The robots are coming, and they're coming for our jobs....

Or are they?

Introducing Queen Elizabeth's Knitting Machines

Queen Elizabeth 1

To understand this moment, we need to take a trip back in time. Not to the birth of the internet, or even the industrial revolution. We're going all the way back to 16th century England, where a clever queen was about to inadvertently kick off centuries of economic confusion.

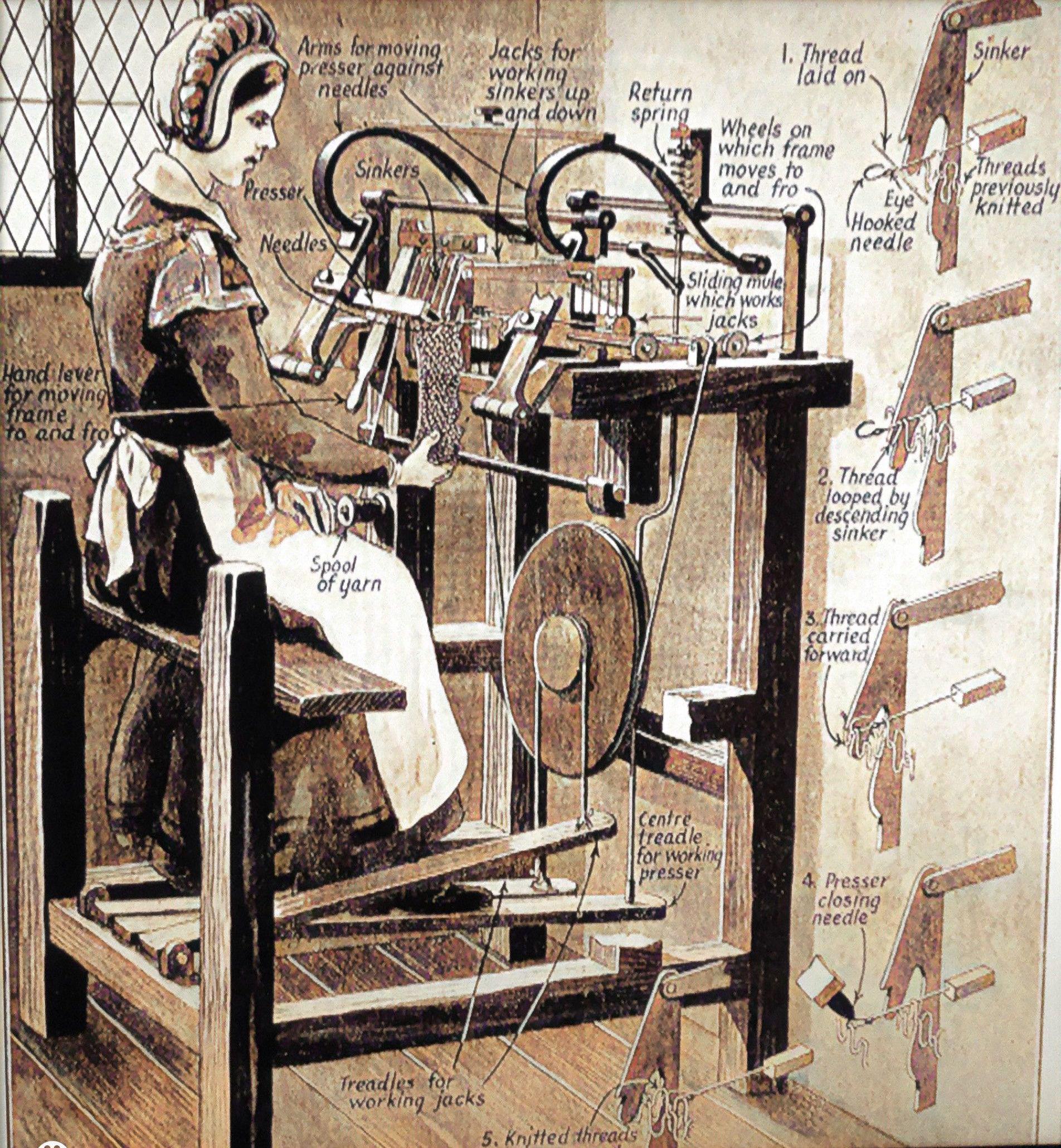

Knitting Machine from 1589

Queen Elizabeth I, concerned about the rise of mechanical knitting machines and their potential to put her subjects out of work, refused to grant the inventor, William Lee, a patent.

"Consider thou," she told him, "what the invention could do to my poor subjects. It would assuredly bring to them ruin by depriving them of employment, thus making them beggars."

Sound familiar? It should. It's the same argument we're hearing today about AI and automation. It's also the same argument we heard about computers, about assembly lines, about the printing press. Each time, the fear was the same: there's only so much work to go around, and if machines start doing it, what will be left for humans?

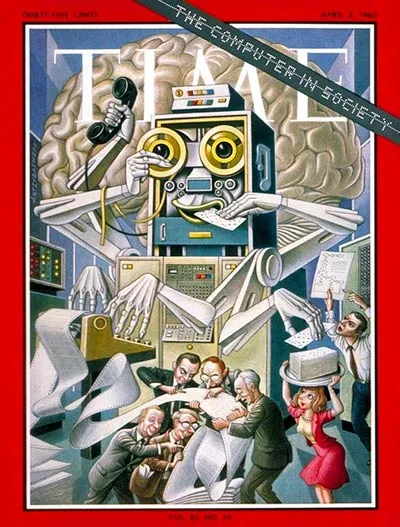

Time Magazine Cover for Computers in 1965

Men such as IBM Economist Joseph Froomkin feel that automation will eventually bring about a 20-hour work week, perhaps within a century, thus creating a mass leisure class. Quote from 1965 about the impact of computers

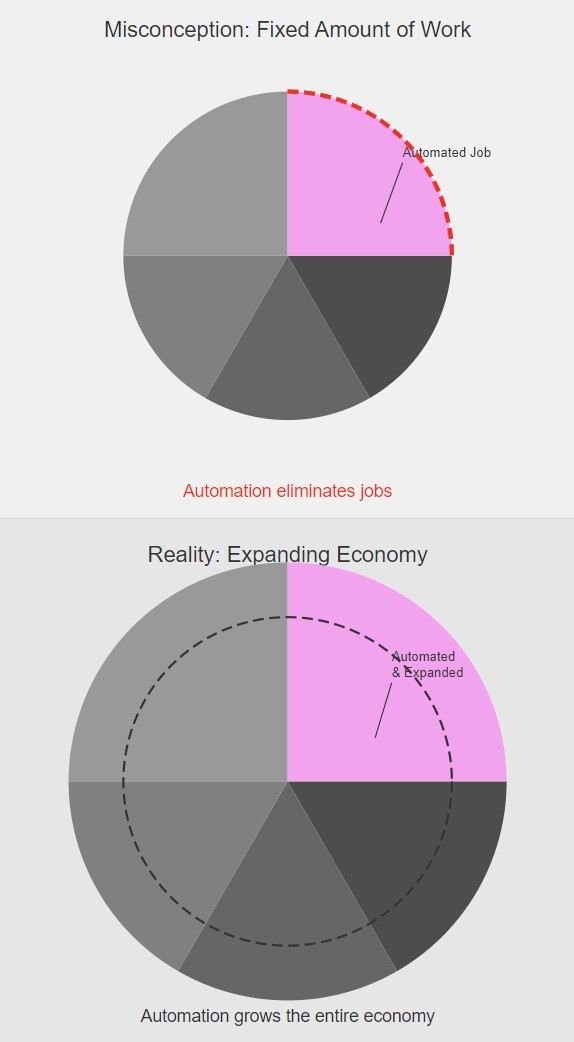

Introducing the Lump of Labour Fallacy

This, my friends, is the lump of labour fallacy in action. It's the mistaken belief that there's a fixed amount of work in the economy. Like a pie that, once sliced, can feed only so many. But here's the kicker: the economy isn't a pie. It's more like a sourdough starter—feed it, and it grows.

Lump of Labour fallacy depicting a growing pie and a fixed pie

So relating this back to the present, something amazing is happening. AI is writing code. But it's not replacing programmers—it's augmenting them. Suddenly, we can prototype faster, solve complex problems more efficiently. And all those ideas for apps and services that seemed too time-consuming before? Now they're possible.

Vintage postage stamp about the growing pie of work. See Ai allowed me to create this!

Across industries, we're seeing the same pattern. AI is taking over routine tasks, but it's also creating new opportunities. Data analysts are becoming data scientists. Marketers are becoming AI strategists and yes, programmers are becoming AI developers.

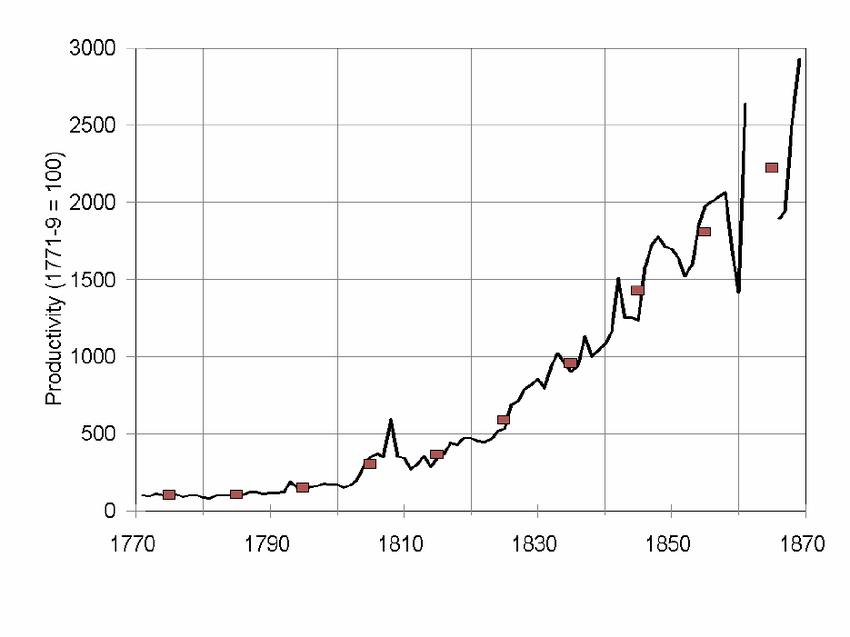

But here's where it gets really interesting. Remember Queen Elizabeth's knitting machines? They didn't destroy the textile industry—they revolutionized it. By the 19th century, England was producing cloth on a scale previously unimaginable, employing more people than ever before.

Graph of weaving productivity

The same thing is happening now. As AI takes over routine tasks, we're free to tackle bigger challenges. Climate change. Space exploration. Curing diseases. Problems we couldn't even conceive of solving before are now within our grasp.

Conclusion

So the next time you hear someone claim that AI is going to steal all our jobs, remember: the economy isn't a lump. It's not even a pie. It's a living, growing thing, and we're all gardeners. The tools may change, but there's always more work to be done. The question isn't whether there will be jobs in the future. It's whether we'll be bold enough, creative enough, and adaptable enough to do them.

After all, if a 16th century queen could worry about automation, and we ended up here, imagine where we might go next. The future of work isn't a zero-sum game. It's an adventure. And it's just getting started.

Postage Stamps

With every article now I would like to include a postage stamp that I have created. This is a new hobby of mine and I hope you enjoy them.

The idea is that in the future I can look back and see all of the stamps that I have created and remember the articles that I have written.