View it here on Amazon

Summary of the Book

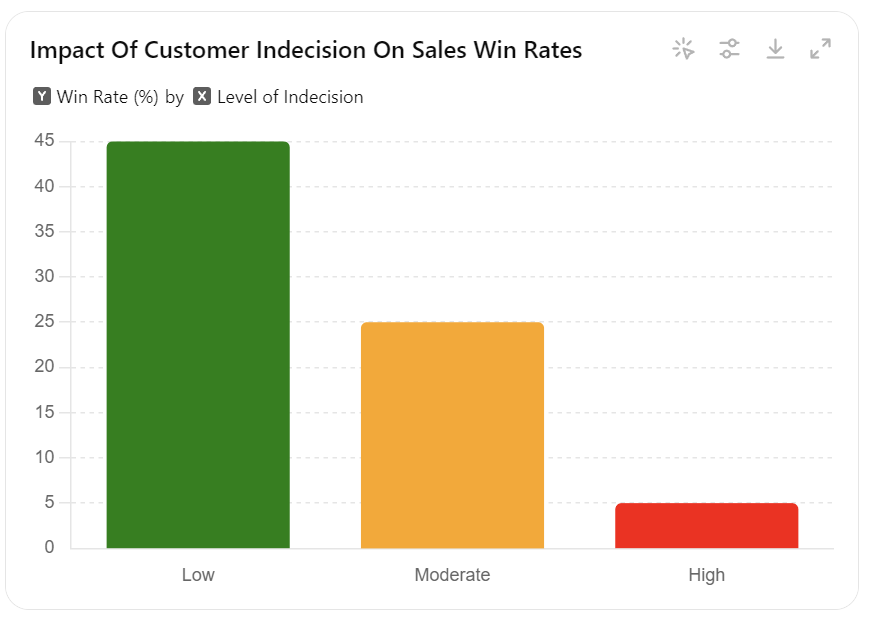

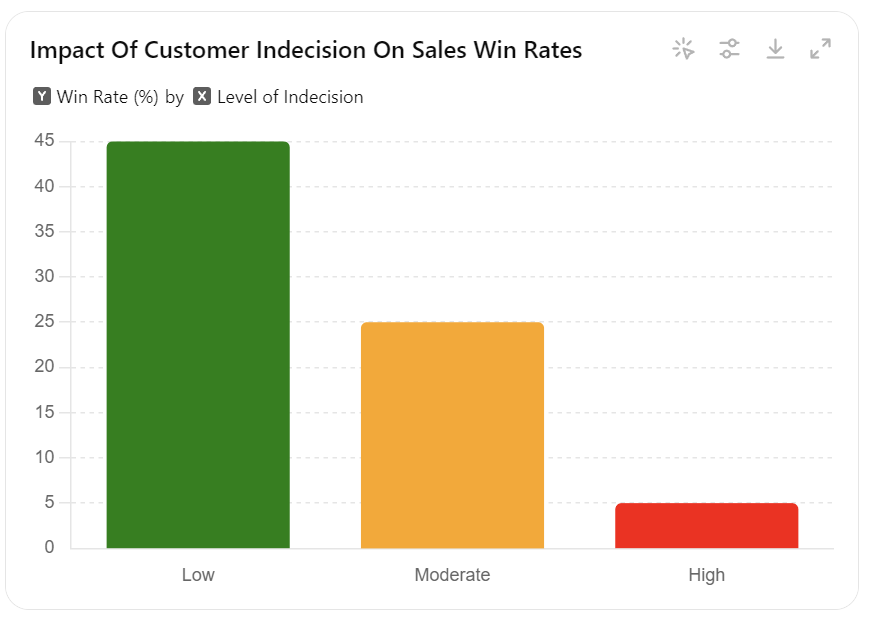

Nearly 87 percent of sales opportunities contain either moderate or high levels of indecision. And it is toxic: as indecision increases, win rates plummet.

The Jolt Effect is a transformative guide that dives into how high-performing salespeople effectively tackle customer indecision to close more deals. The book highlights the concept that most sales losses aren't because customers prefer a competitor or see no value in the offering but because they struggle to make decisions.

Customers, it turns out, are much less worried about missing out than they are about messing up.

Key Concepts

Understanding Customer Indecision

High performers recognize that the primary enemy in sales isn't the competition or even a lack of customer interest—it's the customer's own indecision. This indecision often stems from fear of making the wrong choice, which can be more paralyzing than having no options at all.

In our research, we found that anywhere between 40 percent and 60 percent of deals today end up stalled in “no decision” limbo. To be clear, these are customers who go through the entire sales process—consuming valuable seller time and organizational resources, perhaps even engaging in extended pilots or proof-of-concept trials—only to end up not crossing the finish line.

The JOLT Methodology

The book introduces the JOLT methodology, a framework designed to help salespeople nudge customers out of indecision:

- J – Judge the indecision: Identify if the customer is truly indecisive or just being polite.

- O – Offer a recommendation: Provide a clear and strong recommendation to guide the customer.

- L – Limit the exploration: Restrict the number of options to avoid overwhelming the customer.

- T – Take risk off the table: Mitigate perceived risks to make the decision easier for the customer.

Customer indecision, however, is driven by a separate and distinct psychological effect called the omission bias, which is the customer’s desire to avoid making a mistake.

Applying the JOLT Methodology

Judge the Indecision

The first step is accurately assessing whether the customer is stuck in indecision. This involves understanding their hesitations and concerns. High performers use empathetic questioning to uncover these underlying issues.

Offer a Recommendation

Instead of bombarding the customer with endless options, high performers offer tailored recommendations. This approach helps simplify the decision-making process and positions the salesperson as a trusted advisor.

Limit the Exploration

To avoid decision fatigue, it's crucial to limit the exploration phase. This means presenting a few well-curated options that align with the customer's needs and preferences, rather than an overwhelming array of choices.

Take Risk Off the Table

Addressing and mitigating perceived risks can significantly ease the customer's anxiety. High performers do this by providing guarantees, showcasing customer success stories, or offering trial periods.

Where overcoming the status quo is about dialing up the fear of not purchasing, overcoming indecision is about dialing down the fear of purchasing.

Applying the JOLT Methodology in Software Consulting

Example 1: Selecting a Technology Stack for a Custom Software Project

Judge the Indecision

During the initial meetings, you notice the client is hesitant to choose between several technology stacks. They express concerns about future scalability and maintenance.

Offer a Recommendation

After understanding their requirements and business goals, you recommend using a popular and well-supported stack like MERN (MongoDB, Express.js, React, Node.js). You explain how this stack's robust community and scalability align perfectly with their long-term needs.

Limit the Exploration

Instead of discussing numerous technology options, you focus on comparing MERN with one other stack, highlighting why MERN is a superior choice based on their specific requirements.

Take Risk Off the Table

You offer a proof of concept (PoC) development phase, where you will build a small, but functional, part of their project using the MERN stack. This PoC helps them visualize the benefits and reduces their fear of making the wrong choice.

But, that one in particular—“I need to think about it some more”—proved to be more highly correlated with lost deals than any other across the tens of thousands of utterances we isolated in these calls. This phrase, statistically speaking, is the kiss of death.

Example 2: Implementing a CRM System

Judge the Indecision

The client is unsure about which CRM system to implement, fearing that a wrong choice could disrupt their sales processes and lead to significant costs.

Offer a Recommendation

Based on their existing workflows and integration needs, you recommend Salesforce. You detail how Salesforce's customization capabilities and robust integration options can meet their specific requirements.

Limit the Exploration

Instead of presenting all possible CRM solutions, you limit the discussion to Salesforce and one other option, clearly showing why Salesforce is the best fit.

Take Risk Off the Table

You suggest starting with a smaller deployment in one department to see how it fits their needs. This trial period helps the client feel more confident about the decision without committing fully upfront.

Instead, the only thing they are concerned about is that they may be making a big mistake by purchasing your solution. All of the other concerns sellers try to leverage to motivate action pale in comparison to this. After all, you don’t get fired for losing out on a 10 percent discount or having to wait another month for an implementation window. But you do get fired for spending money on a solution that fails to deliver the benefits it’s supposed to deliver.

Our research shows that the best sellers have figured out that there is a point in the sale where their job is no longer convincing the customer how they’ll succeed by making the purchase; it’s about proving to the customer that they won’t fail by making the purchase.

Example 3: Choosing Between Cloud Providers

Judge the Indecision

The client is stuck between choosing AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud. Their primary concern is cost efficiency and ease of use for their team.

Offer a Recommendation

After evaluating their use cases and team expertise, you recommend AWS due to its wide range of services and cost-effective pricing models that suit their needs.

Limit the Exploration

You compare AWS with only one other cloud provider (e.g., Azure), focusing on specific benefits AWS offers for their particular use cases, such as cost-saving features and ease of integration.

Take Risk Off the Table

You propose a phased migration plan, starting with a few low-risk applications. This gradual approach allows the client to test the waters with AWS before fully committing, thereby reducing their anxiety about making a wrong decision.

Types of Status Quo preference

There are three types of status quo preference that salespeople encounter, lack of information, valuation problems and outcome uncertainty:

-

Lack of Information: The customer feels anxious or confused about not having enough information to make an informed decision. They may ask for more demos, reference calls, or conversations with subject matter experts.

-

Valuation Problems: The customer struggles to compare different options or configurations, gets distracted by new features, or expresses confusion about which option to choose.

-

Outcome Uncertainty: The customer is skeptical about the returns they'll see from their purchase, asks for ROI projections, or expresses concern about the risk or investment involved.

The fear of loss

Customers are more likely to make a decision to avoid loss than to realize a gain. This fear of loss drives their decision-making process and can lead to indecision when they perceive a high risk of making the wrong choice.

In their research, Kahneman and Tversky found that we place more weight on loss that is the result of doing something wrong (what are known as “errors of commission”) than we do on loss that is a result of failing to do something right (known as “errors of omission”).

Inaction inertia definition

Inaction inertia is the tendency to stick with the status quo due to past experiences of passing up better options. This inertia makes it harder for customers to act on objectively good options, leading to indecision and missed opportunities.

Qualify the customer based on decision-making ability

There was an interesting concept here about qualifying customers not just based on their ability to buy but also on their ability to decide. This distinction is crucial because customers who struggle with decision-making are more likely to get stuck in indecision, leading to lost deals.

In our interactions we often find that large organisations have a lot of decision makers and the decision making process can be slow and cumbersome. This is where the ability to decide becomes crucial. Sure they might have the budget to buy, but can they make a decision?

In our study, we found that high performers were disproportionately more likely to disqualify opportunities in which the customer seemed intractably indecisive.

A lot of customers are indecisive and so in that case make a recommendation.

High performers know that customers who are indecisive are looking for guidance, not more choice. And so, they take a decidedly different approach. Rather than asking confused customers what they want, they instead tell them what they should buy (e.g., “These are all good options, but personally, here’s what I would do if I were you”).

Start small

This is an interesting concept. High performers recommend that customers start small, generate early wins, and then expand from there. This approach helps customers overcome outcome uncertainty by reducing the perceived risk of making a large investment upfront.

Finally, in contrast to much of the conventional wisdom out there that high-quality sales are always bigger and more expansive, we found that high performers can overcome outcome uncertainty by recommending to customers that they instead start small, generate early wins, and then expand from there. Ironically, they ultimately sell more by selling less up front.

what our best reps understand is that, ironically, they will sell more by selling less.” More often than not, this leader explained, his best reps will actually talk customers out of additional options before giving them a price—they’ll

Be aware when customers don't show clarity

“A warning sign for me,” one star rep told us, “is when customers struggle to explain how they created their short list of vendors they’re talking to. They typically won’t tell me who else they’re talking to, but they should be able to tell me what the ‘must have’ criteria were that they used to filter down to a smaller number of providers—as well as which criteria were deemed less important. If they can’t explain their criteria, that tells me they’re not going about this in a way that’s going to lead to a decision.”

Show a lot of options upfront and then narrow down

While it seems like minimizing the choice set for customers would make it easier to get to a purchase decision, there is also ample data to suggest that customers are actually drawn to the idea of more options, especially early on in the buying journey. It’s only later in the journey that these same choices become problematic.

This approach is shown in the famous jelly experiment by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper. They set up a table with 24 different flavors of jelly, and 60% of visitors stopped by to sample one. However, only 3% ended up buying a jar. On another day, they offered only six types of jelly, and 40% sampled one, but 30% ended up buying a jar.

The solution isn’t to eliminate choices altogether for customers; it’s to know when it’s time to shrink the consideration set in order to drive the customer toward a decision.

Note in order to do this the book recommends that you proactiely make recommendations.

But, as effective as this approach was, we found that high performers more frequently offered their recommendations before the customer expressed any confusion about how to value the different choices in front of them.

The 40-70 rule

But how much information is “enough” for a customer to make a decision? A good rule of thumb is the “P = 40 to 70 rule.” This concept was coined by General Colin Powell, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and US secretary of state, who wrote and spoke extensively about leadership principles over his career. “Use the formula P = 40 to 70,” Powell explains, “in which P stands for the probability of success and the numbers indicate the percentage of information acquired. Once the information is in the 40 to 70 range, go with your gut.” In Powell’s experience, making decisions with less than 40 percent of the information required is just guessing, and waiting until you have more than 70 percent is just delaying. “Don’t take action if you have less than a 40 percent chance of being right,” he says, “but don’t wait until you have enough facts to be 100 percent sure, because by then it is almost always too late.

Three key skills of high performers

The book highlights three key skills that high-performing salespeople use to limit exploration and guide customers toward a decision:

- Owning the Flow of Information: High performers take control of the conversation and guide customers through the decision-making process, providing valuable insights and recommendations.

First, high performers in our study were far less likely to cede control of the conversation to others inside their own organizations. Specifically, we found that top sellers relied less on subject matter experts like solution engineers, product leaders, and customer success managers in their calls than did average performers, who tended to bring in subject matter experts much earlier.

“We have tremendous experts across our organization,” one rep told us, “but the minute I bring those folks into a call, I start to erode the customer’s perception of me as an expert. It’s like the old saying goes, ‘You get delegated down to the person you sound like.’

Second, we found that when high performers did bring in other experts, the percentage of time they allowed those experts to speak during sales calls was orders of magnitude lower than on similar calls run by average performers.

- Anticipating Needs and Objections: They proactively address customer concerns and objections, offering rebuttals before the customer even articulates them.

Third, we found that, early on in the sales process, high performers were more proactive than their peers in suggesting additional reading and sources of information the customer should consult to help them come down the learning curve—and, importantly, these were often not their company’s own marketing materials or thought leadership content. On one call, for example, a top rep laid out a reading list for his customer: “I find that many of my customers go online and try to ‘self-educate’ around this technology but there’s so much content out there that it can be really overwhelming and people just end up confused at a higher level. I’m going to send you a few links to some pieces that I always recommend to people looking at this technology for the first time.

The vast majority of the time, we found the customer offering signals that they were getting cold feet, and, instead of stopping to root out the cause of their indecision, the seller just kept plowing ahead with their pitch. In many respects, it’s human nature to avoid bringing up bad news. But high performers showed a remarkable lack of trepidation in opening the Pandora’s box of customer concerns, fears, and objections. Instead, they dove right in. High performers were unafraid to probe when they sensed customer hesitation—knowing that an unstated objection has just as much potential for derailing a sale as a stated one—and, once objections were surfaced, they displayed a high level of comfort in openly disagreeing with the customer, pointing out misunderstandings or putting misplaced concerns to bed.

- Practicing Radical Candor: High performers are honest and direct with customers, even when it means challenging their assumptions or decisions. They focus on what's best for the customer, not just making a sale.

“We sell to CFOs and it’s natural to feel intimidated when you’re selling to somebody who’s been doing this job for longer than you’ve been alive, but here’s the thing: they may know more about being a CFO, but even our least-tenured rep knows a ton more about our product and this technology than any prospective customer.

remember that our customers aren’t looking for us to teach them how to do their jobs, they’re looking for us to help them be smart consumers of a technology they don’t know much about.”

And the last quote about it that sums it up really well.

Finally, there is “radical candor.” This is the sweet spot, as Scott explains. Salespeople who practice radical candor are focused on what’s best for their customers and aren’t afraid to tell them when they’re headed in the wrong direction. These reps are unafraid to tell a customer when they’re wrong or when they’re about to make a mistake. In our research, we found that they were professional but firm in telling the customer that what they were asking for wasn’t necessary or that the additional data they were seeking wouldn’t resolve the concerns they were hoping to resolve.

Average win rates

This suprised me:

As a reminder, the average win rate for sales interactions in our study was 26 percent.

As a side note, I'm always suprised by how little organisations track their win rates. It's such a crucial metric to understand how well your sales team is performing.

Interupt, get excited and overtalk

These are not words that I would have associated with good salespeople but the book highlights that high performers are quite comfortable interrupting the customer and talking over them when they feel it is important to get the conversation back on track.

A call with a top seller just sounds different. In our study, average performers tended to defer to the customer in conversations—saving their product and market insights for moments in the conversation when customers asked questions. High performers, by contrast, were far more assertive in demonstrating their expertise. Where average sellers waited to speak until spoken to, high performers looked to proactively find ways to share their experience and knowledge with the customer.

High performers, unlike their average-performing colleagues, are quite comfortable interrupting the customer and talking over them when they feel it is important to get the conversation back on track.

Under the same thread, they talk about a concept called cooperative overlapping.

While this might seem like rude behavior on the part of the seller, that’s not what was going on at all. Instead of impolite overtalk and interruptions, we found that what was happening is what linguists refer to as “cooperative overlapping.” This term was coined by Georgetown University linguistics professor Deborah Tannen, who explains that “cooperative overlapping occurs when the listener starts talking along with the speaker, not to cut them off but rather to validate or show they’re engaged in what the other person is saying.”[6] Tannen says another way to think about cooperative overlapping is “enthusiastic listenership” or “participatory listenership.”

It's all about engagment and not meerly listening

This is a critical concept for sellers to understand: listening is important in sales, but if you want to close a deal, engagement is actually more important. Indecisive customers need an active, engaged conversation with a salesperson to get them over the hump. Too often, salespeople see it as more beneficial to defer to the customer, to sit back and listen.

High performers don’t hesitate to share their expertise, they don’t allow for “dead air,” and they engage in cooperative overlapping with their customers. A high-performer conversation is neither a lecture nor an interrogation. It’s an active and engaged dialogue between two equals—a spirited conversation one would expect to hear between two good friends who’ve known each other forever.

There is limited “downtime” in a high-performer sales conversation. When the customer is talking, she is met with verbal acknowledgment while she’s conveying her thoughts. We found, quite literally, thousands of instances of the rep saying things like “Absolutely,” “Yeah, I hear what you’re saying,” “Yup, makes sense,” “Oh,

The importance of the middle option

better to offer multiple options to the client—one “all-in” option, one moderate option, and one “toe-dipping” option. While they would be attracted to the potential returns of the larger proposal, he would proactively steer them toward the middle option as a better way to get started. “Many of my peers back then never figured this out and would instead go ‘whale-hunting,’ putting only the biggest, most expensive and riskiest proposals in front of their clients because this was, they thought, the fastest way to hit their numbers. But those deals never close and, if they do, the client is immediately second-guessing their decision. Most of those folks aren’t here anymore.”

The rise of the travel agent

Enter the travel agent—or, as they’re called today, “travel advisors.”[1] When faced with so many options and overwhelmed by the fear of making a costly mistake, today’s customers increasingly seek the help of an expert who can help them navigate different options and ultimately instill confidence that the customer is going to have a great experience. More than anything, this is what the curious case of the travel agent—their rise, fall, and ultimate resurgence—teaches us: being a customer in today’s world is hard, and overcoming indecision doesn’t require a seller as much as it requires an advisor who can take them by the hand, lead the way, and help them arrive at a successful outcome.[2]

The Principal-Agent Problem

The Principal-Agent Problem The principal-agent problem is when one person (the agent) is able to make decisions on behalf of another (the principal), but an incentive misalignment or conflict of interest causes the principal to believe that the agent is making decisions that benefit only themselves. This problem typically arises when there is information asymmetry between the agent and the principal—that is, when the agent has more information than the principal about the decision that’s on the table, leading the principal to feel as if something’s being kept from them.

One of the most impactful was suggesting that the customer not “overbuy” where they don’t need to—an idea we also discussed in the previous chapter. Customers will often come in looking for a more expensive product or service than what their specific needs demand, and it represents a prime opportunity for the seller to develop trust and demonstrate credibility by suggesting the customer spend less, not more.

Be positive even about your competitors

Another technique for building trust and overcoming the agency dilemma is offering positive feedback on a competitor’s offer or even outright recommending a competitor’s product or service as a better fit for the client’s needs. In one transactional sales call, the customer referenced a better price point offered by a competitor for what seemed like an identical service plan. “That is a great price for that plan and I wouldn’t blame you for taking it.

Thaler and Sunstein found that an effective way to nudge people toward a decision is by offering something called a “default option.” Defaults work because they turn what would normally be deliberative choices into instinctual ones—in other words, they take decisions off of the reflective track and put them onto the automatic one. Why? Because a default represents the path of least resistance;

importantly, a default serves as an implicit recommendation that is being made by a trusted authority. Clearly, somebody smarter than we are chose this as the default option—and they have our best interests in mind—so who are we to disagree?

Make it easy for the customer to say yes

Confidently asking for the business works the same way for salespeople. At once, it positions saying yes and signing the agreement to move forward as the default option. Saying yes becomes the easy choice whereas saying no feels like a hard gearshift,

“I’d like to get you on the calendar for implementation and onboarding. Should we go ahead and get things rolling? If you’re in agreement, I can send you the DocuSign right now.” “This is a great choice for your business. I’d say we should go ahead and get it locked in. I can take your credit card information whenever you’re ready.” In many respects, there is nothing more central to being a salesperson than asking for the sale.

Walt Disney once remarked, “Whatever you do, do it well. Do it so well that when people see you do it, they will want to come back and see you do it again, and they will want to bring others and show them how well you do what you do.”